The term Accords nouveaux (new tunings) indicate tunings for the lute which are used at the latest from 1622.

Lute is a generic term for types of plucked strings which form an extended family. What the instruments of this family have in common is the body in the form of a drop (or pear) cut in half, with a soundboard which is more or less flat. The neck extends from the narrow end of the body and shows a variety of forms: with a bend-back pegbox, and/or with different forms of neck extensions for bass courses.

In Europa the lute was played at least from the thirteenth century on (this excludes Al Andalus, the so-called ‘Moorish’ Spain, and other European areas which were at least temporarily part of the Arabo-islamic culture, and where the lute was brought to as an integral part of this culture much more early). During the centuries to follow many different forms developed for different types of usage and the demands to be met in connection with these. It vanished from musical life around 1800, only to slowly reappear around the end of the nineteenth century. The book The Lute in Europe 2 contains a survey of the different forms of the lute, how and why these developed, and an introduction into tablature notations. On this homepage you will find an introduction to the lute types which are used for the repertory in Accords nouveaux here.

Basic information on the tuning (French „accord“)

I prefer to speak from nominal tuning because the size of the lute respectively the breaking point of the string material determinate the highest frequency in which the highest string/course of the instrument can be tuned.

If we know the frequency, the next parameter is the pitch, which can vary five halftones: The same lute can be tuned as highest on f', f' sharp, g', g' sharp or a' – and all of these note names indicate the same frequency!

The pitch varies in geographical regions and inside these regions in the different musical functions (see the distinction between Chorton [the pitch for churches] from the clerical environment and Kammerton [chamber pitch] for the courtly / civil environs.

In consequence it's not wise to give a concrete note name (which we normally associate today with a' = 440 Hz). A good idea is to give the intervals between the courses – in other words a relative tuning. For this purpose the Traficante system is a very practical solution: It marks the intervals from course to course with tablature letters. François-Pierre Goy and me adapted this system to the special requirements of plucked instruments (see Tunings – a Survey).

From the Vieil ton to the Accords nouveaux and from there to the Nouvel accord ordinaire (NAO)

The sixteenth-century lute was commonly equipped with six courses tuned in fourths with a major third between the third and fourth course (counting form the highest sounding course down): ffeff in fret positions (for an explanation of this short form of describing a tuning see: Thesis Tunings – A Survey). The pitch to which the courses were tuned depended on the sounding string length of the instrument. The most common nominal tunings are thought either in A (a’ e’ b g d A) or in G (g’ d’ a f c G). This tuning was later called Vieil ton.

In 1638 appears a tuning in which all six most fingered courses are tuned in a complete minor chord. Today, this tuning is called the D-minor tuning (f’ d’ a f d A). This term is misleading, because the size of the lute forces the reachable frequency and therefore the note name. In consequence this tuning is called here Nouvel accord ordinaire or short NAO, given in fret positions as dfedf). The NAO was accepted from c. 1640 on as the tuning of the Baroque lute.

Accords Nouveaux are called those lute tunings which still relate to the Vieil Ton, how far ever they deviate from it, while they are still not related to the Nouvel Accord Ordinaire (NAO). In some cases, Accords nouveaux were in use side by side with the Nouvel accord ordinaire until c. 1710. It would therefore be wrong to understand them as transitional phenomena.

Why the Vieil Ton fell out of use in France (not in Germany) towards 1622, and experiments with different new tunings – the Accords nouveaux – were carried out, finds no explanation in any historic source. We are therefore dependant on hypotheses if we want to explain this phenomenom.

The term Accords Nouveaux goes back to the Ballard collections of 1631 and 1638, both entitled Tablature de Luth de differens autheurs sur les accords nouveaux. There are more tunings then those found in this two prints. Which of these additional tunings may be accepted as Accords Nouveaux and which not, is a matter of opinion. This Website follows, at least for the moment being, François-Pierre Goy who accepted in his thesis twelve tunings as Accords Nouveaux. The list of these tunings can be downloaded here in the form of a PDF file.

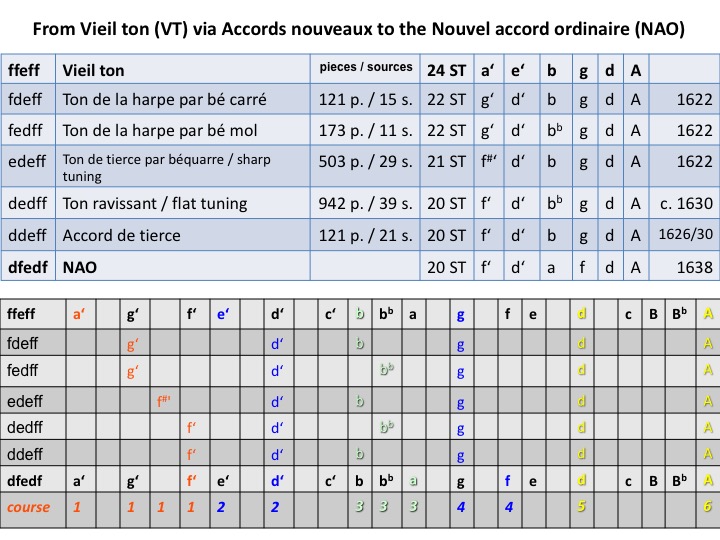

Above the most used tunings from the Vieil ton up to the Nouvel accord ordinaire are indicated. On the left the tunings are given in the Traficante system, then the historical terms are indicated, then the dissemination (f.ex. 121 pieces in 15 sources). The total ambitus from the 1st to the 6th course is given in semitones (24 ST are two octaves). Then an interpretation of the note names is given, thought that the 6th course is tuned in A. At lesat you find the date, when a tuning appears for the first time (but we have to be aware of the big loss of sources and in consequence earlier appearences are possible).

On the chart below the same tunings are indicated, but the different courses in different colours. The Vieil tone uses two octaves (here supposed a’ to A). You can see, that the green coloured 1st course starts at an a’, is lowered to g’, to f’ sharp and finally to an f’. It ist lowered a major third from the Vieil ton to the NAO.

The 2nd and 4th course are lowered a major second, but in the case of the 4th course only as last step to the NAO.

The 3rd course determinates firstly „B quarré“ or „b molle“ – in modern terms major and minor. Later it is lowered to a.

The 5th and 6th course remain stable.

Here you can hear the tunings and detect the historical terms for the accords:

- ffeff: Vieil ton

- fdeff: Ton de la harpe par bé carré

Historical terms:

ton de harpe de B [natural] et Ton de la harpe par [natural] (34-D-Us 132, p. 58 und fol. IVv)

Ton de la harpe par b dur (2-CH Bu 53, fol. 19v)

harpway (36-Board, fol. 32v)

The highest tuning of the lute with 1st string tuned up half a note (1-Balcarres, S. 218 – therefore a variation of the Accord nouveau edeff) - fedff: Ton de la harpe par bé mol

Historical terms:

Ton de la Harpe par b mol, Ton de la harpe par b (34-D-Us 132, p. 66 und IVv)

Ton de la harpe par b mol (2-CH-Bu 53, fol. 25v)

Harpe-way, Tuning flat-way or Lawrence (18-Pickering, fol. 44) - edeff: Ton de tierce bé carré

Historical terms:

Ton de tierce par B [natural] (34-D-Us 132, p. 64);

Tuning Gautier (18-Pickering, fol. 45);

accord nouveau par [natural] quarre (45-Mersenne 1636-I, p. 91a);

B quare (20-S-N 1122, fol. 1);

Pecard (38-CH-Zz 907, fol. 18 and 21v);

sharp; The sharp tun uhich called gautirs tune (13-Wemyss, fol. 26v);

The highest tuening of the lute (1-Balcarres, S. 216; compare fdeff) - dedff: Ton ravissant / flat tuning

Historical terms:

[Accord nouveau] par b mol (45-Mersenne 1536-I, p. 91a)

B Mol (20-S-N 1122, fol. 1)

flat, flatt (13-Wemyss, fol. 32v etc.)

flat tuning (26-GB-Ob E 411, fol. 78)

Le ton rauissant (31-US-R 186, p. 55)

bémol (38-CH-Zz 907, fol. 6 etc.)

Flat-French-Tuning (49-Mace 1676, p. 83)

vieux Bemol simple (F-AIXméj Ms. Rés. 17, fol. 97) - ddeff: Accord de tierce

Historical term:

Accor de tierce (34-D-Us 132, p. 56)

Par Becard hormy la huitiesme et la chante[relle] par Bemol (38-CH-Zz 907, Fol. 12v

flat saue the 3 sharp (13-Wemyss, Fol. 32v) - dfedf: NAO (nouvel accord ordinaire, thought from A it's the D-minor-tuning; but there exist pieces fro Baroque lutes in different pitches and in consequence different sizes (f.ex. Radolt with chanterelles tuned in c', e' flat and f'). So the tuning is to understand as a relative tuning!

The Accords nouveaux are not an isolated phenomen of the lute: Lyra viol, Mandore and Baroque guitar

During the period the Accords Nouveaux were employed for the lute, the music of the Lyra Viol, a variety of the Viola da Gamba, also became a field of experimentation with many tunings, some of which correspond the lute lute’s Accords Nouveaux. Similarly, the tunings of the Mandore and of the Baroque guitar were experimented with. To make comparisons possible, these instruments and their tunings are also registered. Here links to the introductions for the Lyra viol, the Mandore and Baroque guitar.

It is certain that in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century a change in musical esthetics took place, and that the lute was treated in new ways even with respect to actual playing technique. Also, the lute instrument used for playing the solo repertoire grew in the number of courses to 11 or even 12, and the bass courses from the sixth down were tuned in a diatonic scale from 1611 on.

The solo music of the lute, the Lyra viol, Mandore and Baroque guitar was almost exclusively notated in tablature. This meant that to keep different tunings in use was not difficult, and that the tuning used in a piece of music at hand could be derived from the tablature.